(5.4)

TOWARDS A THIRD CINEMA

(Africa-

Morocco

)

[Documents and Reviews]

“The Hour of the Furnaces”, Towards a Third Cinema, O. Getino and F. Solanas, excerpt from Cine, Cultura y descolonizacion, Siglo Veintiuno Editores, Buenos Aires, 1973

“Just a short time ago it would have seemed like a Quixotic adventure in the colonized, neocolonialized, or even in the imperialist nations themselves to make any attempt to create films of decolonization that turned their backs on or actively opposed the System. Until recently, film had been synonymous with show or amusement: in a word, it was one more consumer good. At best, films succeeded in bearing witness to the decay of bourgeois values and testifying to social injustice. As a rule, films only dealt with effect, never with cause; it was cinema of mystification or anti-historicism. It was surplus value cinema. Caught up in these conditions, films, the most valuable tool of communication of our times, were destined to satisfy only the ideological and economic interests of the owners of the film industry, the lords of the world film market, the great majority of whom were from the United States. Was it possible to overcome this situation?”

Read the full manifesto in English here , first published in Spanish in 1969 in the Tricontinental magazine, OSPAAAL.

︎

Anti-Imperialist Films: A Guide, Guy Hennebelle, 1975, Martineau Hennebelle collection

“We can hope, however, that with the emergence of Third World countries, new kinds of cinema will appear and, like what the Vietnamese and Algerians have done and what the Palestinians are beginning to do, without forgetting a number of independent Latin American filmmakers, will nurture the production of films promoting an essential “decolonisation” of minds in the field of cinema. The contribution of political cinema from Western Europe and North America is also important.”

In the foreword to his guide to anti-imperialist films, the politically-engaged journalist and film critic Guy Hennebelle, also director of the Cinémaction review, reflects on the state of the world, which he divides up as follows:

“A. a first world is made up of two superpowers who compete to extend their hegemony: the United States and the Soviet Union.

B. A second world is made up essentially of what have become secondary imperialisms: the countries of eastern Europe, Canada, Japan.

C. Finally, a third world, which is the Third World, made up of nations that have been pillaged and devastated by Western and Japanese imperialism, accompanied by social-imperialist Russia, which uses new tactics to infiltrate itself and extend its branches in all directions.”

facilitating the work of activists looking for films “that help develop awareness or lead to rallying against imperialism.” In terms of Moroccan films, the guide recommends two films by Souheil Ben Barka, Mille et une mains [A Thousand and One Hands, 1972] and La guerre du Pétrole n’aura pas lieu [The Oil War Won’t Happen, 1975], as well as the magnificent Mémoire 14 (1971) by Ahmed Bouanani, a montage film using colonial archives which the censors turned into a short film by cutting out a significant part of the film concerned with Berber resistance and the Rif War.

︎

![]()

![]()

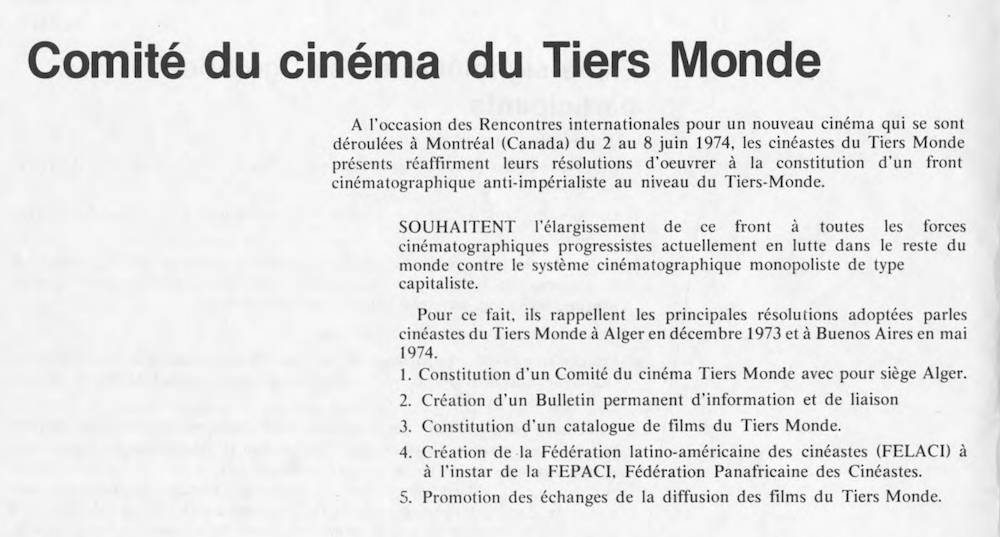

Resolutions of the Algiers (1973) and Buenos Aires (1974) meetings of the Third World Cinema Bureau,

André Pâquet collection, 1974, Cinémathèque québécoise collection

December 1973, Algiers: meeting and launch of the Comite Cine del Tercer Mondo / Third World Cinema Bureau

May 1974: meeting of the Third World Cinema Bureau in Buenos Aires

Resolutions of the Algiers (1973) and Buenos Aires (1974) meetings of the Third World Cinema Bureau,

André Pâquet collection, 1974, Cinémathèque québécoise collection

December 1973, Algiers: meeting and launch of the Comite Cine del Tercer Mondo / Third World Cinema Bureau

May 1974: meeting of the Third World Cinema Bureau in Buenos Aires

︎

Posters for the International Conference for a New Cinema,

designed by Noël Cormier, 1974, Cinémathèque québécoise collection

The RENCONTRES INTERNATIONALES POUR UN NOUVEAU CINEMA [International Conference for a New Cinema] in Montreal in 1974 aimed to bring together filmmakers and collectives who questioned the role and means of cinema. The Third World Cinema Bureau took part in the conference.

PROGRAMME

“We are at a turning point in the history of cinema. At 75-years-old, cinema has just become aware of its true role in the contemporary political context. This awareness was first demonstrated by a questioning of the traditional cinematic structures (Estates General, France, 1968). With the appearance of national cinemas (especially those of small producing countries and Third World countries), the hegemony of the great capitalist cinemas was confronted with a new reality: a cinema in transformation that must develop a praxis which ensures its continuity.”

Programme of the Rencontres internationales pour un nouveau cinéma, Montréal : Film Action Committee, 1975TEXTS

"A cinema of progress and awakening, which must firstly be national. A cinema that first helps at home, and is then international. Useful at home, and then useful to the cause of other peoples leading more or less the same struggles against colonialism and imperialism. And in an even more distant perspective, one that helps the struggles of the working masses in the colonizing countries themselves. I believe that these objectives are the steps we must take towards a cinema of decolonization. Avoiding these steps could lead us to become captive to the enemy cinema, whereas we must respond in stages to the two functions whose focus I have mentioned above, namely: neither art nor commerce, but first of all a readable and awakened cinema. To take over the western distribution circuits, or not, is a question that we also ask in a second phase. This is because these circuits are based on profitability and risk making us fall back into commercial cinema, where reality is cast aside."

Eléments pour une théorie du cinéma africain [Towards a Theory for African Cinema] by Ferid Boughedir“What does cinema represent for me, as someone provisionally French, but also foreign, living as I do in a country because the contradictions of history have brought me there? What does it mean to make films for a filmmaker from an underdeveloped country? One must thus ask the fundamental question: what does cinema represent for the Third World? What does making films mean to a Third World filmmaker? (…)”

Le rôle du cinéaste africain [The Role of the African Filmmaker] by Med HondoCahiers des Rencontres internationales pour un nouveau cinéma [Notebook of the International Conference for a New Cinema], Montreal: Film Action Committee, 1975, Cinémathèque québécoise collection

Click here to read the full texts by Med Hondo, Ferid Boughedir and Tahar Cheria [in French]

VIDEOS

Tahar Cheriaa (Tunisia) speaks about the Pan African Federation of Filmmakers (FEPACI) and the various fronts of the struggles for cinema on the African continent. June 1974. Extract, 5’57. Original format : 1/2 inch reel video tape. Cinémathèque québécoise collection

Declaration of the Third World Cinema Bureau, Algiers, read by Lamine Merbah (Algeria) and backed by Tahar Cheriaa (Tunisia) on behalf of the FEPACI. June 1974. Original format : 1/2 inch reel video tape. Cinémathèque québécoise collection

RESOLUTIONS

Resolutions of the Third World Cinema Committee at the International Conference for a New Cinema, 1974, Cinémathèque québécoise collection

Excerpt from Notebook 2 of the International Conference for a New Cinema, directory of groups, 1974, Cinémathèque québécoise collection

The directory of groups was intended to be a tool “contributing to the empowerment and continuity of a cinema which has a role to play in the historic process that we are encountering.” It can be viewed in full here.

“The main objectives of the FE.PA.CI (Pan African Federation of Filmmakers) are:

1. To work to break down barriers in a continent still suffering from the vestiges of colonialism

2. To support the emergence of truly national cinemas

3. To fight against the Franco-American stranglehold on distribution circuits.

These objectives are mainly intended to create ties between the continent’s filmmakers, to help them come together, and build national associations.

The FE.PA.CI is therefore a tool for the defence and promotion of all African national cinemas, from the south of the continent to north of the Sahara, just as it is interested in those of its sister nations in the Middle East.”

︎

Tiers Monde review, Vol 20 n°79 Audiovisual and Development, 1979

Special dossier by the Cinémaction team, “The Impact of ‘Third Cinema’ in the World”,

In the African and Arab worlds, a clear convergence by Ferid Boughedir, Martineau Hennebelle collection

Special dossier by the Cinémaction team, “The Impact of ‘Third Cinema’ in the World”,

In the African and Arab worlds, a clear convergence by Ferid Boughedir, Martineau Hennebelle collection

Ten years after the publication of Solanas and Getino’s manifesto for a socially and politically interventionist cinema, the Cinémaction review team, led by Guy Hennebelle, studied the impact of Third Cinema in Africa and the Arab world in particular, especially through the article by Tunisian critic and filmmaker Ferid Boughedir,. The article looks at the filmmakers who were continuing to reflect on the relationship of their cinema to the struggles and social realities of their countries and offers an interesting perspective on the differences between socially interventionist cinema in Latin America and in Africa.

“The fundamental difference between the theory of third cinema and interventionist cinema as practised in Africa and the Arab world undoubtedly lies in the disparity of contexts: the Latin American continent has certainly been colonized and neo-colonized economically and politically, but it has never experienced a brutal breakdown of identity as suffered by Africans and Arabs, subjected to total colonization: as far as we know, the intellectual and artistic elites in Latin America do not express themselves in American! As a result, many African and Arab films are devoted to an affirmation of cultural identity, a concern that could seem folkloric to a foreign gaze, or to an exacerbated nationalism that could seem concerning elsewhere.”

Ferid Boughedir, 1979︎

Le Tiers Monde en Films [The Third World in Films], special issue, CINEMACTION and TRICONTINENTAL, 1982

MOROCCO by Jean-Pierre Garcia and Halim Chergui (Guy Hennebelle), Martineau Hennebelle collection

In this article, which was published in 1982 in the review CINEMACTION for its special issue with the TRICONTINENTAL magazine, the authors allude to the obstacles to the emergence of Moroccan cinema, particularly the difficult socio-economic context and the absence of a national drive for production.

“From a population of 22 million inhabitants, in 1981, three and a half million were unemployed and piled into slums. After the relative democratisation that accompanied the period of reconquest of the formerly Spanish Sahara, oppression grew considerably worse, culminating in the Casablanca massacres of 1981. In September of the same year, the leader of the UFSP (Socialist Union of Popular Forces) was imprisoned, joining the political detainees that the regime had been keeping in its jails for years.”

The mentioned films are therefore “the fruits of individual efforts by determined artists”. Wechma [Traces] by Hamid Benani (1970), Mille et une mains [A Thousand and One Hands, 1972] and La guerre du pétrole n'aura pas lieu [The Oil War Won’t Happen, 1975] by Souheil Ben Barka, two attempts at political films, are discussed, as well as Moumen Smihi's very accomplished first film El Chergui [Violent Silence, 1975], and Ahmed el Maanouni's films Alyam, Alyam (Oh the Days!) (1975) and Transes [Trances, 1981]. Through the music group Nass el Ghiwane, this film takes up the search for a Moroccan identity by reconnecting with the authenticity of ancient and popular traditions, which refuse both "Western acculturation" and "Middle Eastern-Turkish delight".

The Cinémaction review, co-founded by Guy Henebelle and Monique Martineau in 1978, reflected on socially interventionist cinema, which considers the relations between films and life, and attempts to draw cinema and (political) action closer together. Cinémaction was particularly interested in feminist, activist, and experimental cinema, as well as film from non-dominant regions, such as African cinema.

Copyright © 2020 / Léa Morin — CINIMA3 / Talitha